I have been mucking about with some programming lately and I only just realized that the work I had been doing to get my average price on trades so I can enter it into my trade log was easily automated. The below Excel (2010 is the version I use) macro has made my life a little easier so I am sharing it here. This can be used with the ‘trade’ output of DAS Trader Pro (which I am currently using with Centerpoint Securities) but with slight changes could be used on the output from Sterling Trader Pro or other trading platforms. There are easier ways to get the summaries, but I make sure to record trades I make in my trade log with details including my trade plan and post-trade evaluation — most of the time I’ll put together all the trades in each ticker to save time and because I’m trading the stock with one strategy. So for my purposes I like having the average price (including fees) shown neatly.

First, start with how the data should be formatted prior to the macro working. Go to “Trade” in DAS Trader Pro and then click “Trades”. Select the columns and copy and paste into an Excel worksheet named “scratchpad” (and make sure to paste into column B). Then hit Control + A to select the entire range of data and run the macro (I have it hotkeyed on my computer to Control+P). This will create a new worksheet, run a pivot table, copy the pivot table data, delete the pivot table worksheet, and paste the pivot table data and price per share in an easy to read format in another new worksheet.

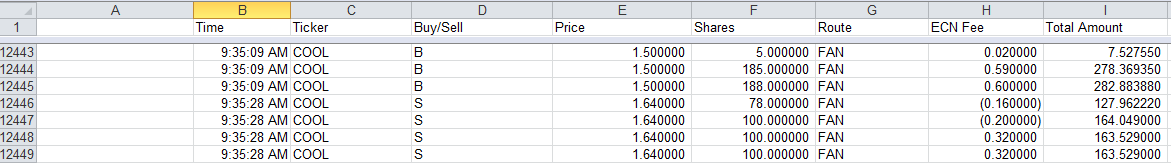

Here is how the data should be formatted in your trade report that you paste into Excel (you do not need a header row):

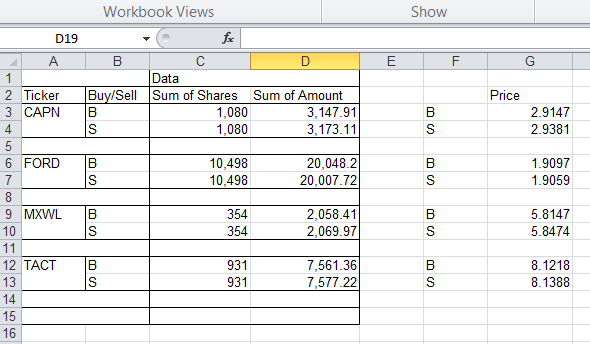

And below is how the data will be output:

Obviously, you can use this same basic code framework to get lots of other data easily (such as ECN fees, etc). The one thing this code will not do is account for per-trade fees. I don’t have them at Centerpoint (clearing through ETC) so I didn’t program them. Also, make sure you enter your per-share commission into the code. Use this code at your own risk — I provide it without warranty or support.

Warning: if you are a programmer you will find my code ugly. You have been warned.

Below is the code:

Sub DAStraderAvgPrices()

‘

‘ DAStraderAvgPrices Macro

‘ For this to work you need to copy pasta the following columns from DAS into the ‘sheet ‘scratchpad’

‘Time | Ticker | Buy/Sell | Price | Shares | Route | ECN Fees | Amount of trade

‘Those columns all must be there in that order or it will mess lots of things up.

‘The trades must be pasted into column B and then select all the trade info ‘(control+A)

‘

‘Dim myRange As Range

Dim i As Long

Dim HeaderRange As Range

Dim HeaderPasteRange As Range

Dim TopLeft As Range

Dim objTable As PivotTable

Dim objField As PivotField

Dim rng As Range

Dim ws1 As Worksheet

Dim pt As PivotTable

Dim rngPT As Range

Dim rngPTa As Range

Dim rngCopy As Range

Dim rngCopy2 As Range

Dim lRowTop As Long

Dim lRowsPT As Long

Dim lRowPage As Long

Dim PivotTableSheet As String

Dim celltxt As String‘this is my commission rate

commission = 0.0035Set myRange = Selection

‘sort by column C then D (ticker then buy/sell)

myRange.Sort Key1:=Columns(3), Order1:=xlAscending, Key2:=Columns(4) _

, Order2:=xlAscending, Header:=xlGuess, OrderCustom:=1, MatchCase:= _

False, Orientation:=xlTopToBottom

‘the above works! Yay!‘this section calculates the cost basis (including ECN fees and commissions) of each fill

For i = myRange.Rows.Count To 1 Step -1

Set BuySell = myRange.Cells(i, 3)

If BuySell.Value = “B” Then

myRange.Cells(i, 8) = (myRange.Cells(i, 4) + commission) * myRange.Cells(i, 5) + myRange.Cells(i, 7)

ElseIf BuySell.Value = “S” Then

myRange.Cells(i, 8) = (myRange.Cells(i, 4) – commission) * myRange.Cells(i, 5) – myRange.Cells(i, 7)

ElseIf BuySell.Value = “SS” Then

myRange.Cells(i, 8) = (myRange.Cells(i, 4) – commission) * myRange.Cells(i, 5) – myRange.Cells(i, 7)

End If

Next i‘Here we append the header row to the data

myRange.Cells(0, 1) = “Time”

myRange.Cells(0, 2) = “Ticker”

myRange.Cells(0, 3) = “Buy/Sell”

myRange.Cells(0, 4) = “Price”

myRange.Cells(0, 5) = “Shares”

myRange.Cells(0, 6) = “Route”

myRange.Cells(0, 7) = “ECN Fee”

myRange.Cells(0, 8) = “Amount”‘Pivot table time!

‘only uncomment the following two lines when testing on specific region

‘ActiveWorkbook.Sheets(“scratchpad”).Select

‘Range(“B4”).SelectActiveWorkbook.Sheets(“scratchpad”).Select

myRange.Cells(0, 1).SelectSet objTable = ActiveSheet.PivotTableWizard

Set objField = objTable.PivotFields(“Ticker”)

objField.Orientation = xlRowField

objField.Position = 1Set objField = objTable.PivotFields(“Buy/Sell”)

objField.Orientation = xlRowField

objField.Position = 2Set objField = objTable.PivotFields(“Shares”)

objField.Orientation = xlDataField

objField.Position = 1

objField.Function = xlSum

objField.NumberFormat = “##,###”Set objField = objTable.PivotFields(“Amount”)

objField.Orientation = xlDataField

objField.Position = 2

objField.Function = xlSum

objField.NumberFormat = “##,###.##”‘Pivot tables with multiple data fields have hidden field “data” —

‘adding the below line makes it display correctly

objTable.AddFields Array(“Ticker”, “Buy/Sell”), “Data”‘Copy the Pivot table and paste it into a new worksheet as values

On Error Resume Next

Set pt = ActiveCell.PivotTable

Set rngPTa = pt.PageRange

‘On Error GoTo errHandlerPivotTableSheet = ActiveSheet.Name

‘If pt Is Nothing Then

‘ MsgBox “Could not copy pivot table for active cell”

‘ GoTo exitHandler

‘Else

Set rngPT = pt.TableRange1

lRowTop = rngPT.Rows(1).row

lRowsPT = rngPT.Rows.Count

Set ws1 = Worksheets.Add

Set rngCopy = rngPT.Resize(lRowsPT – 1)

Set rngCopy2 = rngPT.Rows(lRowsPT)rngCopy.Copy Destination:=ws1.Cells(lRowTop, 1)

rngCopy2.Copy Destination:=ws1.Cells(lRowTop + lRowsPT – 1, 1)

‘End IfIf Not rngPTa Is Nothing Then

lRowPage = rngPTa.Rows(1).row

rngPTa.Copy Destination:=ws1.Cells(lRowPage, 1)

End Ifws.Columns.AutoFit

‘Stopping Application Alerts

Application.DisplayAlerts = False‘delete pivot table sheet

Sheets(PivotTableSheet).Delete‘Add in some formatting and get price per share for buys/sells

Columns(“C:C”).ColumnWidth = 13.71

Columns(“D:D”).ColumnWidth = 14.86

Range(“G2”).Select

ActiveCell.FormulaR1C1 = “Price”

Columns(“G:G”).Select

Selection.NumberFormat = “0.0000”

Selection.ColumnWidth = 11.43

Range(“F3”).Select

ActiveCell.FormulaR1C1 = “=IF(ISBLANK(RC[-4]),””””,RC[-4])”

Range(“F3”).Select

Selection.AutoFill Destination:=Range(“F3:F197”), Type:=xlFillDefault

Range(“F3:F197”).Select

Range(“G3”).Select

ActiveCell.FormulaR1C1 = _

“=IF(ISBLANK(RC[-3]),””””,IF(ISBLANK(RC[-5]),””””,RC[-3]/RC[-4]))”

Range(“G3”).Select

Selection.AutoFill Destination:=Range(“G3:G202”), Type:=xlFillDefault‘Loop through table to clear all rows that contain “Total”

Last = Cells(Rows.Count, “D”).End(xlUp).row

For i = Last To 1 Step -1

celltxt = Cells(i, “A”).Text

If InStr(1, celltxt, “Total”) Then

Cells(i, “A”).EntireRow.ClearContents ‘ USE THIS TO CLEAR CONTENTS BUT NOT DELETE ROW

End If

Next iActiveSheet.UsedRange.Select

exitHandler:

Exit Sub

errHandler:

MsgBox “Could not copy pivot table for active cell”

Resume exitHandler

End Sub

Disclaimer: I have no position in any stocks mentioned as of this post being published but I may trade them in the future. I am a client of Centerpoint Securities (clearing through ETC). I have no relationship with any other parties mentioned above. This blog has a terms of use that is incorporated by reference into this post; you can find all my disclaimers and disclosures there as well.